BrainPOP Science

A Science Teacher’s Guide to Avoiding Engineering Mistakes

If you had visited my science classroom on a Monday morning in September, I would have told you of course I incorporate engineering into my instruction.

By the middle of Wednesday, my answer would’ve been much different. With so much science content to cover and state tests to prepare for, I’d have said that engineering would just need to wait.

And for me, it did.

In my middle school classroom, engineering was an add-on—something we did at the end of the year, in the tricky time between state testing and summer vacation. At the time, a successful engineering project meant building 30 of the same product from the same set of instructions. I would end up with a closet full of cardboard gumball machines and a room full of students who never got a chance to evaluate, optimize, and iterate on their designs.

💡 Download your own Engineering Design Process poster and/or handout for your classroom.

While engaging students in hands-on projects is nothing to sniff at, the teacher in me sees all of the things I should’ve done better. My first instinct is to burn it down and start over—to never see a cardboard gumball machine or printed set of instructions again. However, the engineer in me sees the potential for iteration, building upon and improving my existing lessons.

3 ways to enrich engineering instruction in your science classroom

1. Reimagine the endpoint

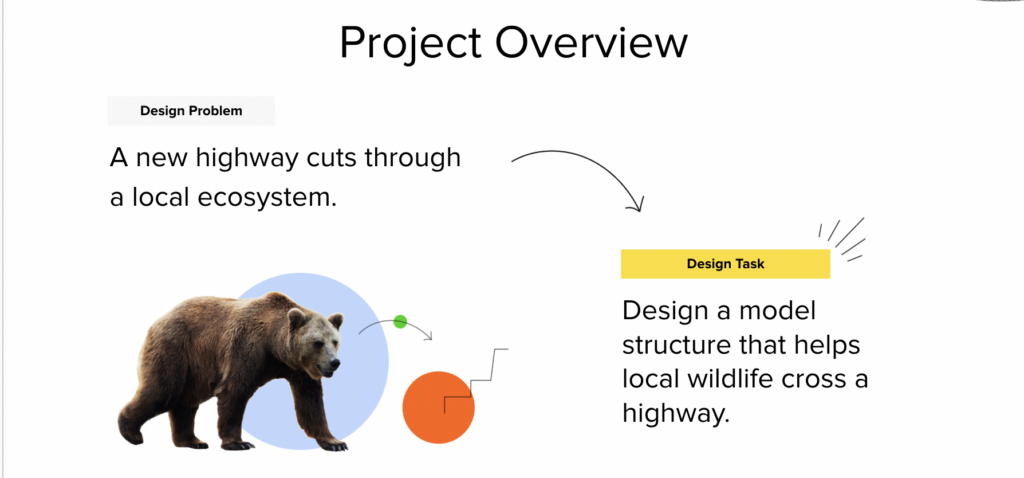

Instead of aiming for a specific product, challenge students to solve a specific problem. When the emphasis shifts from replicating a design to designing a solution, students have a chance to be creative and hone their problem-solving skills. This also allows you to link engineering to a wider range of science topics, including life science and Earth science—domains that are usually left out of product-driven projects.

Example: Instead of tasking students with building a bridge, try asking them to devise a way for wildlife to safely cross a new highway.

2. Adjust the scope

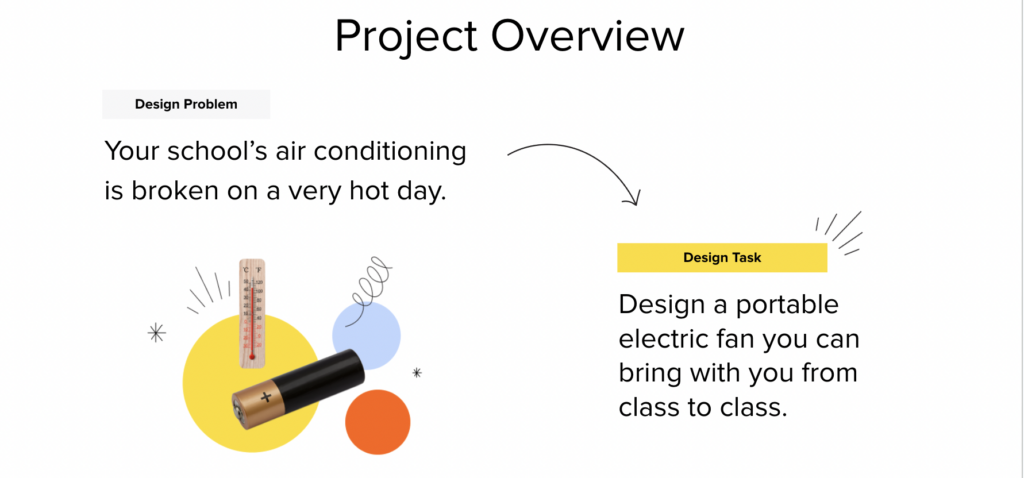

Engineering is a multistep process that flows from brainstorming and research to design, building, testing, re-design, and evaluation. While comprehensive engineering projects provide valuable learning experiences, shorter activities focusing on part of the process can be equally effective, especially when time is limited.

Example: Pose an engineering problem at the beginning of a science unit. For example, before teaching circuits, say: “Imagine that the air conditioning has stopped working on one of the hottest days of the year. Brainstorm ways to design a battery-powered fan to carry from class to class.” At the end of the unit, return to the problem statement. If you have time, you can continue with a full engineering project. If not, ask students to compare their initial ideas with new ones that incorporate their knowledge of circuits.

3. Redefine success

Use rubrics that focus on engineering as a process instead of a product. This multiplies students’ opportunities for success. Consider evaluating how well students:

- Define a problem: Can they articulate the challenge and its constraints?

- Develop a plan: Do they demonstrate a systematic approach to problem-solving?

- Test and analyze: Do they analyze results to inform further design iterations?

- Communicate effectively: Can they clearly explain their decisions and conclusions?

And finally, embrace the adventure. Engineering is often messy, loud, and chaotic, but that’s where the magic happens.

Hannah Bonville is the lead STEM learning designer at BrainPOP. She holds Master of Public Health (MPH) and Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT) degrees, and is a former classroom teacher and pre-service teacher supervisor.